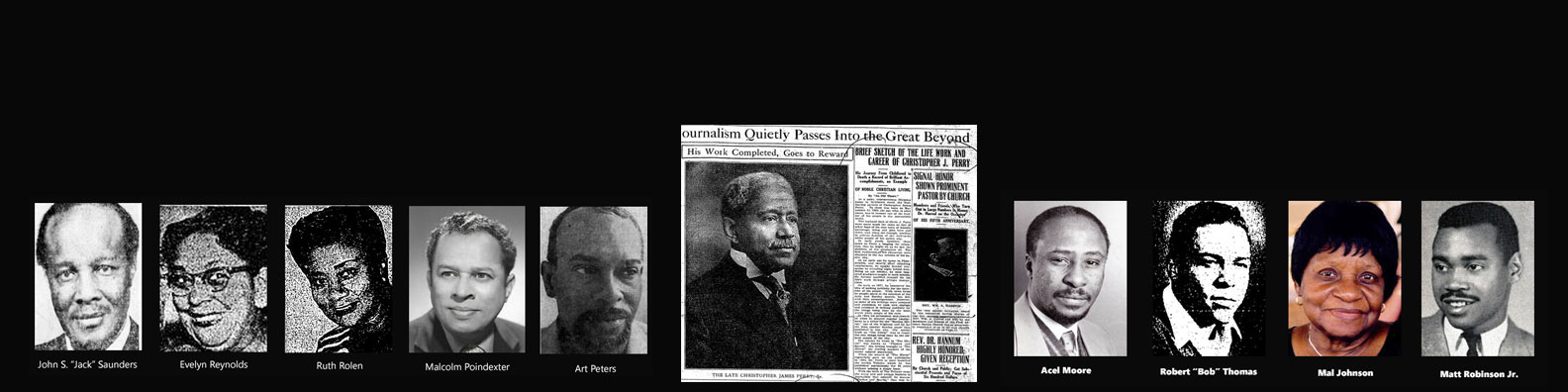

BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2024:

TELLING THE "REAL" STORY OF BLACK LIVES

During Black History Month 2024, NABJ-Philadelphia highlighted some of the pioneering journalists who wrote about the Black community in all of its richness. Our vignettes focused on Black journalists and journalism prior to 1970. We wanted to make sure that the contributions of these heroes were known and preserved. These vignettes were compiled from newspaper articles and other sources. They were written by Sherry L. Howard, an NABJ-Philadelphia founder and its first treasurer.

The Black Press: A stopover and destination for Black journalists

During the first half of the 20th century, most Black journalists in Philadelphia were employed at four major Black newspapers: The Philadelphia Tribune, The Philadelphia Independent, and the Philadelphia offices of the Pittsburgh Courier and (Baltimore) Afro-American.

They easily moved among the newspapers from job to job as reporters and editors. For the most part, these publications were the only outlets providing the means for them to be journalists.

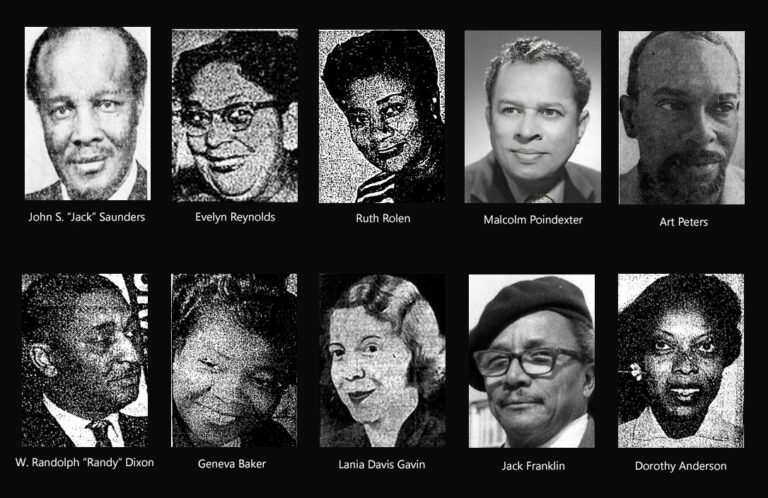

This is a short incomplete list of the journalists who worked at Black newspapers during that time:

Art Peters got his start at The Tribune in 1957 under managing editor John S. “Jack” Saunders. Peters was a reporter and columnist before being tapped as city editor in 1966. He also did commentary for WDAS radio. In 1971 he was hired as a columnist at The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Malcolm Poindexter held several jobs at The Tribune after starting as a clerk. Over 15 years, he was a reporter, photographer, columnist, sportswriter, city editor, business manager and comptroller. He joined the staff of the Philadelphia Bulletin in 1960 but headed over to KYW News radio five years later. He was one of the first reporters hired by the station. A year later, Poindexter was assigned to the Eyewitness News team as a KYW-TV newscaster.

Ed Bradley began his career working evenings at WDAS radio as a disc jockey and DJ while first attending Cheyney University and later as a sixth-grade teacher. He covered the riot along Columbia Avenue in North Philadelphia in 1964. He headed to New York in 1967 for a job with WCBS-TV.

John S. “Jack” Saunders was a mainstay at The Tribune. He rose from paper wrapper in the back room to sports editor, managing editor, editor and president. He was also a columnist. He remained with the newspaper off and on for 30 years. He hosted the shows “On Camera” and “Subject” on WFIL-TV, Channel 6.

Lania Davis Gavin was a reporter at The Independent and the Philadelphia office of the Pittsburgh Courier. She was woman’s editor for The Tribune and wrote the social column “Philly Pepper pot.” She also worked in the advertising department of the Afro-American. Once while at The Independent, Gavin went out to report a story about a missing young woman, found her and returned her to her family. Gavin was a member of the New York-based Negro Writers Guild. Her blond hair was often cited in newspaper descriptions of her. One Black writer called her the “flaming Philadelphia reporterette” in a 1938 column in The Courier.

Geneva Baker was woman’s editor at The Independent and a society columnist at The Tribune.

Dorothy Anderson wrote the “Strictly Politics” column – emphasizing the importance of Black voting – at The Tribune.

Billy Rowe wrote the Billy Rowe’s Network column on a variety of subjects at The Tribune. He also was a writer at the Pittsburgh Courier in the 1930s.

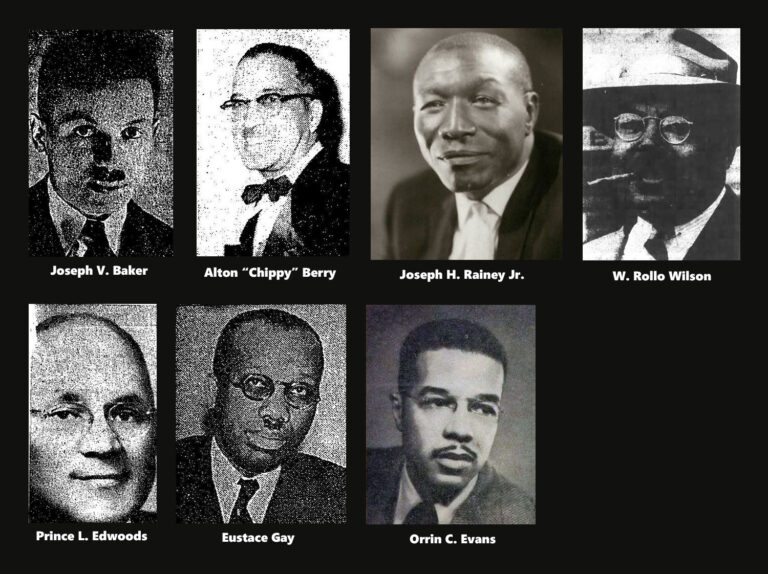

Eustace Gay was another longtime staffer at The Tribune. He began as a proofreader in the 1920s. He held jobs as features columnist, religious editor, secretary and assistant to the editor, managing editor, editor and president. He was at the company for more than 50 years.

Joseph H. Rainey was a sports columnist, writer and editor at The Tribune. He also wrote sports stories for The Philadelphia Record, a white newspaper. He was the grandson of Joseph H. Rainey of South Carolina, the first African American member of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Evelyn Reynolds was a social columnist at The Tribune who wrote under the pen name “Eve Lynn.” An activist, she focused her stories primarily on women.

Ruth Rolen, who wrote under the byline “Ruth Roland,” joined The Tribune at age 14 as a junior editor for its “Kiddies Klub.” She was one of the first Black female reporters to cover City Hall. She also was a police reporter who accompanied officers on nighttime drug raids. In 1944, The Inquirer hired her for temporary street duty after white transportation workers walked off the job to protest the hiring of eight Black trolley drivers. Rolen was city editor of both The Independent and the Afro-American. She was also a religion editor at The Tribune. She was a founder of the Press Club of Black Journalists.

W. Randolph “Randy” Dixon was a sports editor, columnist and managing editor at The Tribune. He was also a managing editor at The Independent and wrote a column for The Philadelphia Daily News. Dixon hosted the show “Ebony Hall of Fame” on WDAS radio in the 1950s. During World War II, he was one of eight war correspondents for the Pittsburgh Courier.

Mamie Robinson wrote the “Women in Politics” column at The Tribune.

Jack Franklin was the staff photographer at The Tribune, remaining with the newspaper for more than 40 years. He was also a freelance photographer whose photos appeared in The Independent, The Afro-American, The Courier, and other local and national publications. His collection of images is housed at the African American Museum in Philadelphia.

A long road: Black journalists at white newspapers and broadcast stations

In 1888, The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin brought on John Stephens Durham as a reporter and eventually elevated him to assistant editor. He most likely wrote about news and events pertaining to Black people.

It appears to have been decades later before another major metropolitan newspaper hired Black journalists – usually no more than one at a time. Joseph H. Rainey, a founder of the Philadelphia Reporters’ Association in 1932, became interracial editor at The Philadelphia Record. When he left in 1935, he was replaced by Orrin C. Evans, who became the first Black general assignment reporter at a metropolitan newspaper in the country. Evans had worked at The Philadelphia Tribune and The Philadelphia Independent, both Black newspapers.

Also starting in 1935, Joseph V. Baker’s articles about Black politics and other issues appeared in the Sunday Philadelphia Inquirer. In 1944, the newspaper dispatched him to cover the Black delegates at the Democratic and Republican National Conventions in Chicago.

These hirings did not create a wave. Nearly two decades later, The Inquirer hired Robert “Bob” Thomas as a clerk/copy boy in 1953. He was promoted to staff reporter after he wrote a story about infiltrating a teen gang. NBC-TV chose his narrative in 1957 for its “Big Story,” a radio dramatization of major newspaper stories and the reporters who wrote them. Actor Terry Carter portrayed Thomas, who appeared at the end to receive a $550 prize and a plaque. Thomas was a City Hall reporter, editor and magazine writer. This was the first “Big Story” by a Black reporter.

By the 1960s and the civil rights movement, white newspapers realized that they needed Black reporters to interface with the people whom they had long ignored. KYW-TV and WCAU-TV went looking for Black women for their newscasts. Trudy Haynes ended up at KYW in 1965, and Edie Huggins found a spot at WCAU a year later.

Here’s a list of some of journalists who were hired:

William “Bill” Thompson joined The Inquirer staff in 1960 as a clerk/copy boy. He later became the newspaper’s second Black reporter. He eventually filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, citing racial discrimination by the newspaper. The Inquirer settled and agreed to hire three Black reporters.

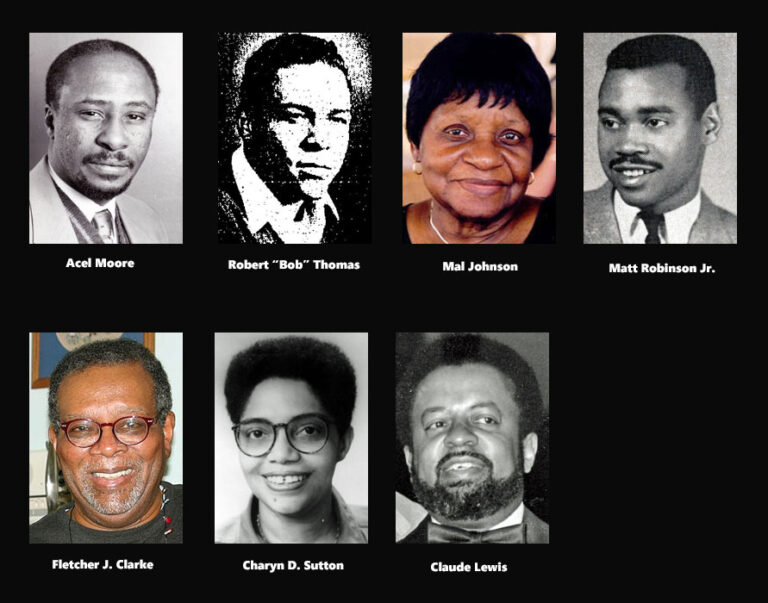

Fletcher J. Clarke started as a clerk/copy boy at the Philadelphia Bulletin in 1961, and eventually was promoted to suburban and police reporter. Clarke stayed with the paper until 1972.

Dennis Kirkland was hired as a clerk/copy boy at The Inquirer in 1962. “The porters and the elevator operators used to give us a hard time, because we were young cats,” Kirkland told Tribune reporter Paul Bennett in 2001, referring to himself and Acel Moore. “But when we got promoted (to reporters) all of a sudden we were their heroes, their role models.”

Acel Moore also arrived at The Inquirer as a clerk/copy boy in 1962. One editor insisted on calling him “Boy.” “I stood my ground by not answering to what was not my name — and took the fellow aside who yelled ‘Boy’ loudest and most frequently,” Moore said in a speech in 2011. “I told him, quietly and privately, that calling a Black man ‘boy’ was a classic, racist insult, and if he said it again that night, I would meet him after work and we could discuss it outside.” Moore was moved up into a reporting position in 1968 and eventually became a top columnist.

Charles H. Thomas was hired by The Inquirer in 1963. He covered the federal courthouse as a reporter. He had been a general assignment reporter at The Tribune and had worked in the Circulation Department of the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin. In 1969, he died in the crash of a plane that he was piloting.

Claude Lewis joined NBC’s WRCV-TV, Channel 3, in 1965. The station eventually became KYW-TV. Lewis was one of the station’s first Black newscasters but found that being on camera didn’t fit him. He was hired by the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin as a reporter. In 1969, became the first Black columnist at the paper and in the city.

Mal (Malvyn) Johnson got her start at WKBS (Channel 48) in Philadelphia in 1966. When she showed up for an interview for a community-relations position, the personnel manager turned her away because she was Black. The owner of the station called her later and hired her. She wrote stories about club news and hosted three programs. In 1969, she was hired by Cox Broadcasting Corp., becoming its national news correspondent in Washington, DC, in 1970.

Matt Robinson Jr. was a writer, producer and on-air talent at WCAU-TV, starting at the station in 1963. He hosted and produced a weekly TV show for job seekers. His father, Matt Sr., was a postal worker who wrote for The Independent. In 1969, Matt Jr. was host of “Black Book” on WFIL-TV, Channel 6. He created the character Gordon on “Sesame Street” and wrote for the “Cosby Show.”

Charyn D. Sutton became The Inquirer’s first Black female reporter when she was hired in 1970. She remained there for one year. She also worked at The Bulletin. She was a high school columnist for The Tribune.

“If you lived in Philadelphia, you grew up watching Edie Huggins.”

Once she was hired in 1966, Edie Huggins appeared weeknights as the Black female reporter of human-interest stories on WCAU-TV. She remained with the station for 42 years as a news anchor and co-anchor, interviewer of newsmakers, host of public-service shows, investigative reporter and community affairs director.

Born Eddie Lou Thompson in St. Joseph, MO, in 1935, Huggins was a disc jockey at radio station KRES in high school. She attended the University of Nebraska as a music major, spurred by her mother Blanche’s desire for her daughter to be a concert pianist. While in college, Huggins appeared on educational TV programs and sang on campus telecasts.

After two years, she gave up her music major, got married and moved to upstate New York with her husband. She decided to pursue a nursing degree and graduated cum laude with a Bachelor of Science degree in nursing education from the State University of New York in Plattsburgh. The marriage dissolved. Huggins worked at two hospitals in New York City while modeling to bring in extra money to raise her two children.

Huggins landed small roles on TV soap operas, including “The Secret Storm,” The Edge of Night” and “Love of Life.” When the casting staff of the NBC drama “The Doctors” learned that she had nursing skills, she became an unofficial consultant to ensure that the show got the medical procedures right. She also had a few lines in the 1966 film “A Man Called Adam” featuring Sammy Davis Jr., but her part was cut.

While in New York, she met the general manager of WCAU-TV in Philadelphia who was looking to hire a Black female reporter as part of his plan to expand news coverage. (A year before, KYW-TV had hired Black reporter Trudy Haynes). He asked Huggins to audition, and she was hired under a three-year contract. She was the station’s first Black female reporter.

First off, station officials changed her name from Eddie to Edith (Eddie was the name of her father, the only Black pharmacist in her hometown). She didn’t particularly like the new name – “sounds like a maiden aunt,” she later said to a reporter – but accepted it. Huggins joined the station’s “Big News Team with John Facenda” as a features reporter.

A 1970 ad in the (Camden, NJ) Courier Post touted Huggins’ versatility: “Edie might bring you a flower show, or preview the coming fashions, or investigate a career in nursing, or the work of an orphanage. She might talk housekeeping with the governor’s wife or rehabilitation with a drug addict. Whatever the story, she does it with a candid flair.”

“I loved the immediacy (of news reporting), the thing that every day you were dealing with a different assignment, some that were extremely complicated and you had to make it appear simple,” she said.

Ebony magazine in 1966 featured Huggins, Haynes and Joan Murray of WCBS-TV in New York as trailblazers for their positions as newscasters at major TV news operations in the United States.

At WCAU-TV, Huggins hosted several public-service shows, including “Morningside With Edie,” “What’s Happening,” “Horizons” and “Edie’s People.” “Miss Edie,” as she was known, mentored many young journalists.

“I had no mentors when I came into the business in 1965,” she told a reporter. “We must remain mentors to those who follow. Don’t let the footprints we make wash away. We must protect them.”

Huggins died in 2008 at the age of 72.

Trudy Haynes was working as a social worker in Detroit when an old college friend told her about the opening of a new Black radio station. Haynes had never done broadcast before.

She had been featured in an ad campaign for Lucky Strike cigarettes (the first Black model to do so), and she had done some modeling in New York City where she was born. So, she applied for a job at WCHB Radio in Inkster, MI, a suburb west of Detroit, and was hired as a receptionist. Part of her job was filing 45 RPM records. As the station prepared for startup, the manager asked if she’d like to host a show. She accepted.

That was the beginning of a foray into broadcasting that lasted more than 60 years. She was a weather forecaster, newscaster, entertainment and movie reporter, gossip columnist and host of a variety of programs, one of which bore her name. She became a TV personality, especially for the Black community, which invited her to speak, judge contests, offer beauty and fashion tips, and talk about her job as a newscaster. She was a mentor to many aspiring young journalists.

She was born Gertrude Daniels in New York City in 1926. She attended Howard University, graduating with a degree in social work, a field that offered a surer route to employment for Blacks. She applied for jobs at the phone company and the airlines, but was told they were not hiring Black people. Haynes worked as an investigator for the New York Department of Welfare.

Two years later she was in Germany organizing shows for soldiers for the military’s Special Services. Haynes returned to New York and became a probation officer. She eventually moved to Detroit and worked in family services for the city.

At WCHB radio station in 1956, Haynes became women’s editor and hosted a daily program titled “A Woman Speaks” and “Teenie Weenie Time” for children. To her child fans, she was known as “Auntie Trudy,” and her show’s theme song “How Much is that Doggie in the Window” was beloved. Haynes also wrote about beauty for the Michigan Chronicle, a Black newspaper.

Haynes remained there for seven years before branching out into TV at WXYZ, an ABC Network station in Detroit, as its “Weather Girl” in 1963. She became the country’s first Black weather forecaster. “Here I was doing prime time doing the weather, and I didn’t know the first cloud from a sunburst. But you do what you have to do,” she told an interviewer. After a while, she became a news reporter.

That stint at WXYZ didn’t last long. She was recruited by KYW-TV and became the first Black TV newscaster in Philadelphia when she joined the station in 1965 as a reporter. She was not warmly accepted by viewers or some in the male-dominated newsroom (she attributed the latter to her nontraditional background). The offenders were few, and their antagonism was based on her sex rather than race, she said in interviews.

Haynes focused on the Black community, telling the stories of their lives beyond crime and tragedy. “We needed to tell our own stories about our own people,” she told a Philadelphia Inquirer reporter. She also interviewed major political and entertainment figures, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., President Lyndon Johnson, Muhammad Ali, Jackie Kennedy Onassis, Barry Goldwater, Hubert Humphrey and Tupac Shakur.

In an interview with the singer Billy Paul, who made “the other woman” famous in his 1972 song “Me and Mrs. Jones,” she asked him “Who is Mrs. Jones?” – a question on the minds of many of the song’s fans.

A year after arriving in Philadelphia, Ebony magazine profiled Haynes, Edie Huggins (hired in 1966 by WCAU-TV in Philadelphia) and Joan Murray of WCBS-TV in New York as newscasters who could hold their own. In that October 1966 edition, Ebony dubbed them “TV News Hens.”

For three consecutive years in the 1970s, Haynes was a judge for the Miss America pageant. She founded the Trudy Haynes School of Total Grooming & Model Placement Service for girls and women.

Haynes – affectionately known as “Miss Trudy” – retired from KYW in 1998 and continued to host TV programs. She died in 2022 at age 95.

In 1932, Joseph V. Baker of The Philadelphia Tribune and Julian St. George White of The Philadelphia Independent called together journalists of the Black press to form a mutual organization.

The group held its first meeting on Oct. 21, adopting a constitution and governing laws, and electing officers. They were writers and advertising men from The Tribune, The Independent and The (Baltimore) Afro-American. The group named itself the Philadelphia Reporters’ Association.

Officers chosen were White, president; Joseph H. Rainey Jr. (Tribune), vice president; Baker, secretary, and Eustace Gay (Tribune), treasurer. Other charter members were W. Randolph Dixon, Kenton Jackson, Prince L. Edwoods, Harold Harbison and Samuel A. Haynes, all from The Tribune; E.W. Baker, Afro-American, and Alton “Chippy” Berry, Orrin C. Evans and W. Rollo Wilson, all from The Independent.

The organization was open to all men whose primary income came from newspaper work. Women journalists were barred as members and from attending meetings.

During the group’s first banquet in February 1934, 100 guests showed up in freezing weather to hear speeches and to tell the journalists what they thought of them – good or bad. E. Washington Rhodes, editor of The Tribune, was a speaker. At the second dinner in 1935, journalists spoke honestly about the people in the audience whom they covered. The journalists produced a skit depicting the inside of the city room of a Black newspaper.

During its first few years, the organization engaged in issues affecting its members as well as the Black community. It sponsored a forum on the inside workings of newspapers. William N. Jones, managing editor of The Afro-American, was invited to speak at a dinner-smoker about his coverage of the trial of Haywood Patterson, one of the nine Scottsboro Boys charged with raping two white women in Alabama in 1931.

At another meeting, members listened as blackface comedian Sam Manning praised the Black press for supporting Black performers. Roy Wilkins, assistant secretary of the NAACP and a former newspaper columnist, was invited to speak about his undercover experience as a laborer to investigate slave conditions in flood-control camps in Mississippi.

In 1935, the group succeeded in persuading the mayor-elect to issue police press passes to Black reporters. The former mayor and administration had failed to provide them.

In what was described as “epoch-making,” the association hosted a 1934 meeting in Philadelphia of East Coast journalists to form the Eastern Newswriters’ Association. By the time the weekend event was over, a new group was formed. Representatives arrived from Pittsburgh, New York, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Washington and Newark, as well as Opportunity Magazine and the NAACP’s Crisis magazine.

Writing in the Philly Pen Points column in The Afro-American, Bernice Dutrieuille noted the significance of the event. She also mentioned the names of several Black female journalists who were expected to attend: Ferol Vincent Smoot of the Associated Negro Press, Thelma Berlack Boozer of the New York Amsterdam News, Geraldyn Dismond of the Interstate Tattler, Bessye J. Bearden (mother of artist Romare Bearden) of The Chicago Defender, and Sarah Pelham Speaks, who assisted her father in forming Capital News Service.

It’s not clear how long the reporters’ association existed beyond 1935.

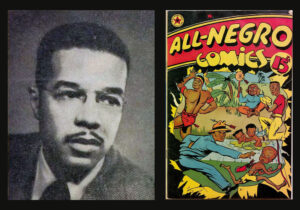

Orrin C. Evans was a pioneering Black journalist, a superb reporter, writer and editor who counseled young journalists on journalism and life. He was considered the dean of Black journalists. He also produced the country’s first comic book for Black people.

Evans was the first Black general assignment reporter at a major metropolitan newspaper in the United States when he was hired by The Philadelphia Record in 1935. The paper had hired a Black interracial editor – who most likely wrote about the Black community – two years before.

Born in Steelton, PA, in 1902 to George and Maude Evans, he moved with his family to Harrisburg when he was six years old and then to Philadelphia. He graduated from West Philadelphia High School and took a year’s accounting course at Drexel Institute. He got a job at age 17 at a local magazine before becoming a reporter for The Philadelphia Tribune around 1922. He left the paper but returned later as its city editor and then managing editor.

He was editor of The Philadelphia Independent, a Black weekly tabloid that was started in 1931 and owned by Forrist White Woodard and his wife, Kathryn “Kitty” Fambro Woodard. He also was managing editor of the Philadelphia Edition of the (Baltimore) Afro-American.

It wasn’t easy for him as a Black journalist: Once, a police officer ordered him out of the station at gunpoint when he was reporting a crime story. Another time, Charles Lindbergh kicked him out of a press conference about the 1932 kidnapping of the pilot’s son.

Evans hung in there because he knew he was paving the way for other Black journalists. A soft-spoken man, he directed them to work hard, be fair and respect the journalism business. He urged them never to become bitter because “bitterness only makes you lose perspective and dilutes your intelligence.” O.C., as he was called by his friends, was not a rabble-rouser nor was he a revolutionary. He preferred working within the system to bring about change.

He was hired by The Philadelphia Record as a reporter and rewrite man after Joseph H. Rainey Jr., the paper’s interracial editor resigned to become athletic commissioner (Rainey had once written sports for the paper).

In a major assignment in 1944, Evans traveled through the South to write about the mistreatment of Black soldiers, particularly regarding bus transportation to and from camp. His articles are said to have forced the War Department to prohibit segregation on military buses. The Record closed in 1947 after a long strike, in which Evans participated. He was a member of the Newspaper Guild of Greater Philadelphia.

Evans founded All-Negro Comics in 1947, partnering with four other colleagues from the Record. This was the country’s first comic book aimed exclusively at Black readers, giving them characters with whom they could identify. Only one issue was produced, “All-Negro Comics #1.” He faced a roadblock when companies would not sell him newsprint for a second issue.

In 1948, he was hired by the Chester (PA) Times, its first Black reporter. He remained there through its name change to the Delaware County Daily Times. A year later, he was awarded first place in the spot-news category by the Pennsylvania Newspaper Publishers Association for his story about a mass killing on a downtown Chester street. He was eventually named an editor at the paper.

In 1962, Evans was hired by the Philadelphia Bulletin, covering the civil rights movement and city government. He was a familiar face at the NAACP’s annual conventions. In 1971, a month before he died, the organization cited him for his coverage, and 18 Black “newsmen” friends feted him with a surprise birthday party. It was there where he was dubbed “dean of Black newspaper journalists.”

Forrist White Woodard and Kathryn “Kitty” Fambro Woodard were publishers of the weekly The Philadelphia Independent, founded in 1931. The Independent heralded itself in its masthead as “The World’s Greatest Negro Tabloid.”

Forrist Woodard was a founder of the Independent, along with Magistrate Edward R. Henry, State Rep. Walker K. Jackson and Addie W. Dickerson, a nationally known civic and political leader who ran for the state legislature in 1930. Forrist was its first publisher and Kitty Woodard took over after he died in 1958. She is considered Philadelphia’s first female publisher. (Interestingly, another Black paper with the same name was founded in 1884 by G.W. Gardner.)

When Henry and Dickerson left in 1932, several new investors joined the remaining original owners. Two years later, the Independent became a tabloid.

The Independent was a Democratic-leaning newspaper, spurred by the columns of writer Lania T. Davis. The paper was considered more militant and sensational than the Philadelphia Tribune. Like the Tribune, though, it fought for equity in employment and political representation for Black people.

“The Independent was for the masses,” Kitty Woodard told Inquirer reporter Annette John-Hall in 1997. “The Tribune had always been the paper for the upper class. We were militant. We weren’t afraid to take on issues like they were.”

Forrist Woodard was born in Norfolk, VA, in 1886 and moved to Philadelphia as a young man, arriving around 1908. He opened several businesses, including a used-car lot and real-estate company.

He operated the popular White’s Wander Inn, an entertainment club.

A Democrat, he was actively involved in political and civic issues, and was a life member of the O.V. Catto Elks Lodge. According to an article in the Philadelphia Tribune in 1958, he reportedly told the city’s Democratic leadership after a victory in the early 1930s that all he wanted from them was recognition for Black people.

Kitty Fambro was a civil rights activist who didn’t mind getting into trouble for causes she believed in. She protested alongside activist/attorney Cecil B. Moore to force Girard College to admit Black students in the 1960s. She was jailed on a traffic violation after the paper called out a white police officer in the shooting death of a Black boy. She stood her ground and was arrested after a white officer told her to move her newspaper trucks that were blocking traffic. She had no other way to unload her papers, she said.

She came to Philadelphia from Fort Valley, GA, with her family when she was 9 years old. She graduated from William Penn High School in 1929, and married twice, the second time to Forrist Woodard. In the early years of the paper, she wrote a column titled “My Folks,” and put it aside to become a homemaker and mother. After she became publisher, she wrote “Kitty’s Korner” to push for civil rights for Black people.

The couple split up in 1955, three years before he died. In 1964, she sold a controlling interest in the paper to a local attorney and stepped down as editor and publisher. Her two daughters maintained their stock in the company. The paper is said to have ceased publication in 1971. Kitty Woodard died in 2003.

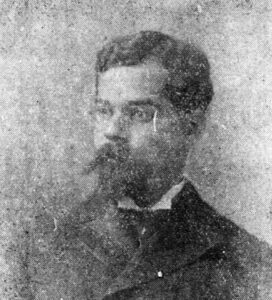

John Stephens Durham was one of the few African Americans during the 19th century to write for a white newspaper. He joined the staff of the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin in 1888 as a reporter before rising to assistant editor.

Described as brilliant, Durham was a lawyer, scholar, linguist (spoke Spanish), educator, journalist and author.

Born in Philadelphia on July 18, 1861, Durham attended public schools in the city. He graduated with honors in 1876 from the Institute for Colored Youth (now Cheyney University), which trained Black students to be teachers. He taught school before he decided to enroll at the University of Pennsylvania to take science courses. He faced racism at the school but used his athletic abilities to survive it. He played on the varsity football team.

Durham graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in 1886, one of the university’s earliest Black graduates. He also enrolled in post-graduate courses in civil engineering. While at Penn, he was editor of the university magazine and wrote editorials.

He worked various jobs to help his widowed mother and pay for his education: night clerk at the post office and writer for The Philadelphia Times, a white publication. He entered Penn’s law school and worked as a janitor there for a short time to make money. In 1888, he got a job as a reporter with the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin and later became an assistant editor. It’s not clear what he wrote about, but normally Black writers on white newspapers covered news of the Black community. Durham was said to have also written editorials at the Bulletin.

He also wrote a column titled “Chit Chat” for The New York Age, a Black publication. He was said to have worked for The Philadelphia Tribune, founded by his friend Christopher James Perry Sr. in 1884.

In 1890, President Benjamin Harrison appointed Durham as consul to Santo Domingo. A year later, he was appointed to replace Frederick Douglass as U.S. minister to Haiti and resigned the position in 1893. Durham resumed his law courses at Penn, graduated and was admitted to the bar, practicing in Philadelphia.

Durham was a contributing writer for several national publications, including Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine and the Atlantic Monthly, where in 1898 he wrote a column decrying the inequitable treatment of Blacks by the labor unions. He wrote the novel “Diane: Priestess of Haiti,” a story about love, romance, tragedy and politics derived from his experiences as a diplomat in the country. The complete novel appeared in Lippincott’s.

In 1898, he published a pamphlet “To Teach the Negro History – A Suggestion,” a look at African Americans dating back to colonial times. It was based on talks he gave at Tuskegee and Hampton schools.

Durham died in 1919 in London, where he had settled.

Christopher James Perry Sr. founded the Philadelphia Tribune as a one-man operation in 1884, telling the stories of Black people through their social, political and church events. The Tribune is the country’s oldest continuously circulating Black newspaper. Along the way, the paper served as a temporary stop and destination for many of the city’s pioneering Black journalists.

Perry was born in Baltimore in 1854 and attended day school there before finding his way to Philadelphia around 1873, according to several newspaper accounts. In a 1980 story on the first 100 years of The Tribune, writer Ed R. Harris noted that little is known about Perry’s precise reasons for moving to Philadelphia, his desire to become a journalist or his early career in the city.

Here is one version of his life, according to several written accounts:

He came to Philadelphia to become a newspaper man against the wishes of his father, who wanted him to be a lawyer. Perry attended night school. Around 1877, he tried to persuade the daily and Sunday white newspapers to publish events in the Black community, but they were not interested.

Perry got a job writing about Black people for a local white Philadelphia newspaper, but there is some discrepancy about which one. Conflicting articles state that in the early 1880s, he wrote for the Philadelphia Mercury and the Philadelphia Mirror. Newspaper articles from the 1920s state that he worked for the Mirror. He wrote a column titled “Flashes and Sparks,” about social news and events for Black readers. When the newspaper closed, he started The Weekly Tribune.

An 1895 article in The Philadelphia Times, written while he was a member of the Common Council (an early form of City Council), offered another version:

Perry was born on Sept. 1, 1864, in Baltimore. At age 16, his father sent him to Philadelphia to attend the Institute for Colored Youth (now Cheyney University) to further his education. He later worked for the Times Printing Company and was a caterer but gave it up.

He began writing a successful weekly political column for Black people for the Sunday Mirror and remained there until the paper folded in 1883. In 1884, he started The Weekly Tribune. He was active in politics, serving on local and state Republican committees. He was appointed as an assistant appearance clerk by two sheriffs. The article ended by stating that he was serving his first term on the Common Council, representing the Seventh Ward.

After the white newspaper closed, Perry continued “Flashes and Sparks” in his newspaper. Robert Still, son of abolitionist William Still, wrote the paper’s first gossip column titled “Bessie to Emma” as an exchange of letters. The unsigned column ran for 10 years and was very popular. Bibliophile/historian William Carl Bolivar wrote the paper’s first column titled “Pencil Pusher”.

Perry had little cash when he started The Tribune. It began as a one-sheet newspaper with him holding every job from publisher to reporter to ad salesman. “Chris Perry’s Paper,” as it was popularly called, slowly attracted readers, its circulation crept up steadily, and ads began to come in. Through the newspaper, Perry fought for better jobs and working conditions for Black people, and more representation in city government.

The paper launched him as a major political player in Philadelphia, with politicians seeking him out as a campaigner and soliciting his advice. Black people persuaded the Republican Party to put him on the ballot for Common Council, and he was elected twice, in 1895 and 1901.

Perry was a founder of Mercy Hospital in Philadelphia and was a president of the National Negro Press Association. He was a charter member of The Citizens Republican Club, a political social organization. He was on the board of directors of the Home for the Protection of Colored Women.

Perry died in 1921 after having been publisher of The Tribune for 37 years. In 1974, he was inducted into the Pennsylvania Newspaper Hall of Fame.

Gertrude Bustill Mossell was one of the most famous Black women journalists of the 19th century. She wrote about female suffrage, women’s rights as well as domestic subjects for both Black and white publications. She also encouraged Black women to become journalists.

Her first article appeared in 1885 in The New York Freeman, the leading Black newspaper at the time, owned by T. Thomas Fortune (the publication later became the New York Age). For two years, Mossell used her voice to promote equal rights for women in a nationally syndicated column titled “Our Women’s Department.” It was the first column written by a woman for a Black newspaper, appearing until 1887.

Mossell was born into a prominent and historically famous Philadelphia family in 1855. She was the aunt of Paul Robeson, an internationally known singer, actor and civil rights activist, and the great-granddaughter of Cyril Bustill, a baker who supplied bread to George Washington’s troops at Valley Forge. She married Nathan Francis Mossell, founder of Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital in Philadelphia.

Mossell taught school in Philadelphia and Camden, and was a founder of the Southwest Branch of the YWCA in Philadelphia.

She gained a national reputation as a contributing writer for local and national newspapers, magazines and journals. They included The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Philadelphia Press, The Weekly Tribune, The Philadelphia Times, The Standard Echo, The North American, The Christian Recorder, A.M.E. Church Review, The Boston Advocate, Our Women and Children, The Women’s Era, The Indianapolis World, The Colored American Magazine and the Ladies Home Journal.

She was editor of the women’s department of The Indianapolis World from 1891 to 1892.

Mossell used her husband’s initials as her byline: Mrs. N.F Mossell.

As a Black female journalist, Mossell was denied membership in Black and white journalists’ organizations. She wrote often about the Black press, including the historical contributions of Black women. At one point, she encouraged Black publications to form a national syndicate to commission and share articles. The idea was discussed among the all-male Colored Press Association (one member was credited with the idea) but never took hold. In 1919, Claude Barnett, husband of activist and journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett, founded the Associated Negro Press, a national news service.

In 1894, Mrs. N.F. Mossell published her first book “The Work of the Afro-American Woman,” a collection of essays and poems on the accomplishments of Black women. Her second was a children’s book titled “Little Dansie’s One Day at Sabbath School,” published in 1902.

In her writings, she spoke highly of her contemporaries, including Wells-Barnett, publisher Caroline Bragg (The Virginia Lancet) and journalist/writer Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. Mossell included a chapter in her first book on the topic of female journalists. Journalism, she wrote, was the “best means of reaching our people, and even making money. Yes, (…) we candidly say, Work, and you can succeed and make money.”

Mossell died in 1948 at the age of 92.

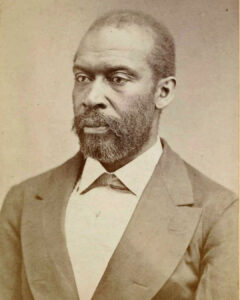

Thomas Morris Chester (or T. Morris Chester) was the country’s first Black war correspondent for a major metropolitan newspaper. He covered Black troops on the front line as an embedded journalist for The Philadelphia Press during the Civil War.

Born in Harrisburg, Chester was hired in 1864, at age 30, to write about Black soldiers in Virginia. He wrote his dispatches under the pseudonym “Rollin” for one year, ending with the war in 1865. He also recruited Black men for the Army of the James, a Union command formed in 1864 with white soldiers of the 24th Corps and Black soldiers of the 25th Corps to participate in an assault on the Confederate capital at Richmond.

His newspaper reports described the human tragedies of war, including the atrocities that the slaughter inflicted on the human body. He also wrote about the Black soldiers’ courage and dignity. (He later settled in New Orleans as a practicing lawyer.)

“When Union infantrymen entered Richmond, the citizens stood, gaping in wonder at the splendidly equipped army marching along under the graceful folds of the old flag,” he wrote for The Philadelphia Press. “The pious old negroes, male and female, indulged in such expressions: ‘You’ve come at last,’ ‘We’ve been looking for you these many days,’ ‘Jesus has opened the way.’”

“The soldiers, black and white,” he added, “received these assurances of loyalty as evidence of the latent patriotism of an oppressed people, which a military despotism has not been able to crush.”

Chester is known particularly for an incident that made the rounds of several white newspapers. A day after he witnessed the fall of the Confederate capital, Chester decided to test out the speaker’s chair in the House of Delegates. The following anecdote appeared as a reprint in the April 11, 1865, Cleveland Daily Leader with the title “‘A Little Story’ with a Moral”.

“A well dressed, well educated, every way respectable looking man, named J. Morris Chester, strolled into the House and with the natural desire every habitue of the Capital at Washington has observed a hundred times, straightway seated himself in the Speaker’s chair. His business in Richmond was to write – in fact he was a correspondent of Forney’s Philadelphia Press – and so he began writing.

Presently a rebel officer, just escaped and out on parole, Lieutenant Butler by name, son of the rebel calvary General Butler, passed the door and saw the correspondent writing. The outrage to the Speaker’s chair (I have neglected to mention that Mr. Chester is as black as a coal, and accompanies the negro troops) was too much for Lieutenant Butler’s blood. Assuming the plantation air, he shouted: “Get out of there, you d—d n___r!” The negro sat perfectly unmoved, and continued his letter (which I sincerely hope was a good one) for the Philadelphia Press. The (wrathful) rebel shouted again, and showered down abusive epithets. The negro wrote on. At last Lieutenant Butler thought it wise, after the established plantation fashion, to proceed further; and with renewed orders to the ‘d—d n—r’ to get out, he undertook to seize him by the collar.

In an instant, the negro, Chester, straightened up out of the chair of the Speaker of the House of Delegates of the ancient commonwealth of Virginia, and duly mindful of the motto of the State, dealt a splendid right-hander full between Butler’s eyes, which sent the rebel sprawling down the aisle. Then, with an eye to business, which, (I specially call Col. Forney’s attention to this point) deserves an increase in salary, the negro resumed the seat of the Speaker of the House of Delegates, and continued his letter to the Philadelphia Press!”

Another version of the story, which was reprinted in William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper The Liberator, quoted Chester as saying: “I thought I would exercise my rights as a belligerent.”